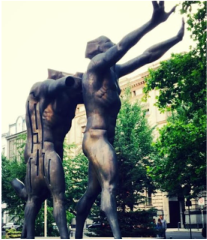

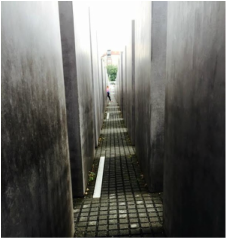

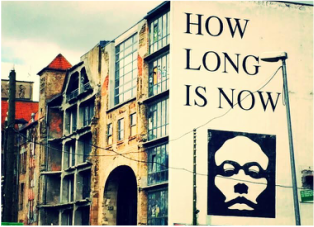

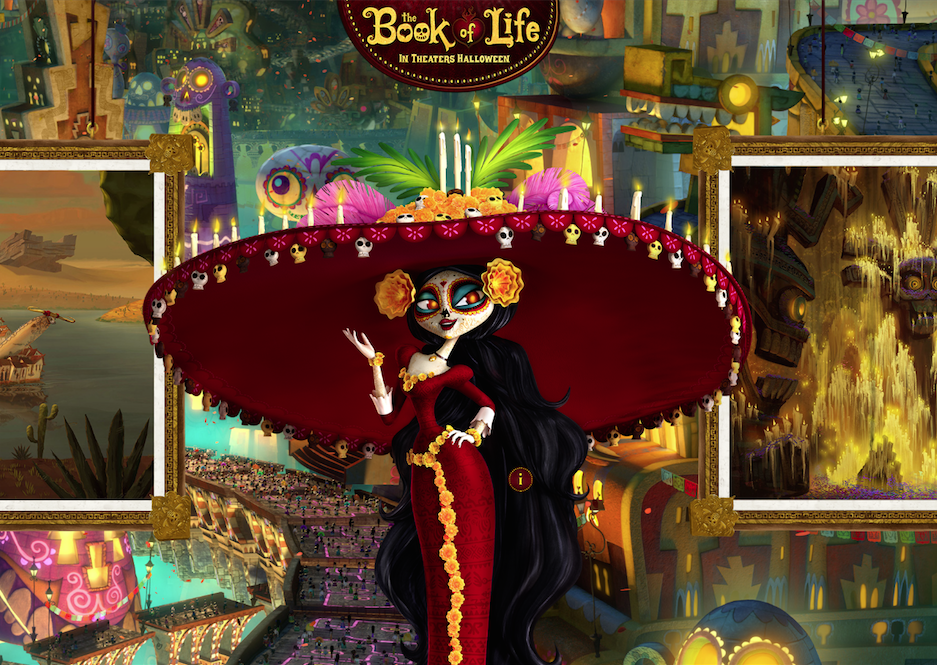

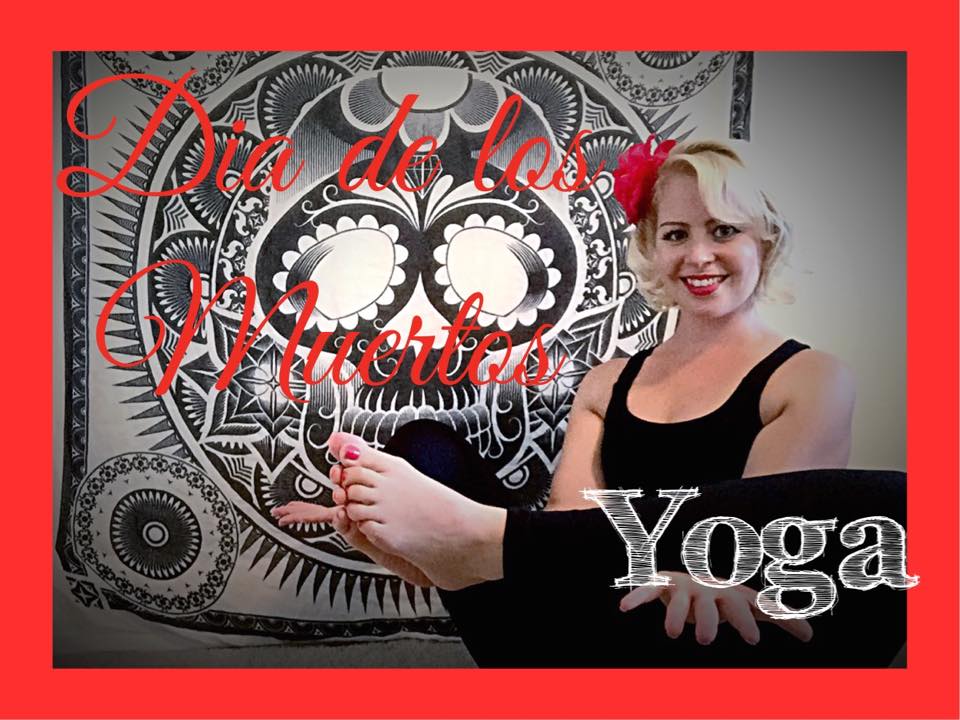

& Dia de los Muertos: Day of the Dead1) Acknowledge Death as Inevitable Are you afraid to die? For many, death implies a cold, unpleasant, and unwelcome end to all we find precious. Our Western society today is both deeply fearful of and uncomfortable with death. We hold powerful attachments to our bodies, relationships, material possessions, and identities that feed into the fear of death. In yoga philosophy, the tendency toward abhinivesha, “clinging to life,” is said to exist in all people, regardless of wisdom, age, wealth, or experience. We cling because we are afraid of the transition of death and of the pain, suffering, and end of the world as we know it. So we devise strategies to avoid thinking about death. In the yoga tradition, deeply acknowledging the reality of death is said to be a source of freedom. By accepting our mortality, we can free ourselves from the bondage of avidya (ignorance). When we acknowledge death as inevitable instead of being blinded by our fear of it, everything else just comes into clearer focus, including the preciousness of each and moment of life (Yoga Journal, Compassionate Dying, by Judith Hanson Lasater). 1) Live for the Present Moment: Now How does the concept of death change the way that we think about life? “It is truly a great cosmic paradox that one of the best teachers in all of life turns out to be death. No person or situation could ever teach you as much as death has to teach you. While someone could tell you that you are not your body, death shows you. While someone could remind you of the insignificance of the things that you cling to, death takes them all away in a second. While people can teach you that men and women of all races are equal and that there is no difference between the rich and the poor, death instantly makes us all the same. You really don’t need more time before death; what you need is more depth of experience during the time you’re given. What if you brought that kind of awareness to every conversation? That’s what happens when you’re told that death is around the corner: you change, life doesn’t change (The Untethered Soul).” 3) Celebrate Life Is death the ultimate end? According to many Mexicans, no, it is not the end. There are two days every year when the gates between the Land of the Dead (also known as the Land of the Remembered) and the Land of the Living are opened. The origins of the modern Mexican holiday are traced to indigenous observances dating back hundreds of years and to an Aztec festival dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl, "Lady of the Dead." She is often associated with owls which are also symbols for wisdom, mystery, and transition. Today in Mexico, the Catalinas (skeletal female figurines) are an echo of this goddess, while skulls are also associated with the Spanish Catholic tradition of marking graveyards. The blending of the Catholic religion create these days as All Souls Day (for every deceased person) and All Saints Day (Day of the Innocents). Similar observances occur elsewhere in Europe, and similarly themed celebrations appear in many Asian and African cultures. 4) Remember the Dead It is important for people to remember you in a happy way. It is believed that you will always live on as long as someone in the living world remembers you. On these days, both contrasting worlds open to visit and to reconnect on a spiritual journey. Beautiful orange flowers called marigolds (Cempasúchil) and candles line spaces from graves to houses so that the lost souls can be guided on these paths back to the world of the living. Day of the dead is a happy day about celebrating a deceased loved one or ones and remembering them by making bread of the dead, their favorite foods and playing their favorite music. People build altars, ofrendas, in their homes or at the graves and fill them with their deceased loved ones’ favorite things, tissue paper decorations, and sugar skulls. Celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events, jokes, and stories about the departed. My friend, JoAnna George, tells a story about how a neighbor met her deceased uncle on this day. A man greeted this woman just outside of the entrance to JoAnna’s family’s home. She walked in and asked who that nice man was. No one knew of any man outside. When the family stepped outside to see, there was no one there. The neighbor described his clothing, demeaner, and humor. It fit the description of her uncle exactly. He came to visit after all! What a wonderful surprise and joyous occasion. 5) You are Not Your Body

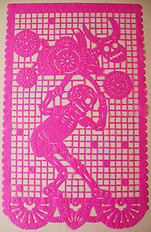

Your body is a material container for your soul. Skulls, calacas in Mexico, were powerful symbols in both Spanish and Mexican Aztec culture in the Middle Ages. In Spain, skulls were used to mark the entrance to graveyards. In Aztec culture, like many ancient cultures, the head was believed to be a source of human power and energy. The Aztecs are recorded to have made human sacrifices to the gods, in order to make sure the sun would continue to rise each day. The remains of these sacrificial victims were kept as relics - skulls and bones were bleached, painted and put on display. Aztec culture believed life on earth to be something of an illusion – death was a positive step forward into a higher level of conscience. For the Aztecs, skulls were a positive symbol, not only of death but also of rebirth. Today, painting your face like a skull is a chance to symbolically overcome your fear of death. La Calavera Catrina ('The Elegant Skull') is a 1913 etching by José Guadalupe Posada. The image showed a skeleton dressed in the finery of a wealthy lady – reminder that even the rich and beautiful carry death within them. Nowadays la calavera catrina is a source of inspiration for women's skull face-painting which is both scary and beautiful at once. Flowers are often incorporated into Dia de los Muertos face-painting skull designs. This mixing of the skull, associated with death and flowers is a symbol in western culture associated with life and love. "Papel picado" is the Spanish phrase for “perforated paper”, referring to the detailed designs that are traditionally hand-cut onto brightly-colored tissue paper. The images on papel picado are always humorous and fun — never scary or sad. The delicacy of the tissue paper means that the decorations won’t last long at all — they are meant to be enjoyed until they fall apart or until it's time to take them down. This non-attachment to longevity is in line with many other Day of the Dead art forms that are only temporary. The Aztecs cut detailed designs into paper made from the bark of trees, such as mulberry and fig. They used these designs, called amatl, as decorations during various festivals (Art-Is-Fun).

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Hannah Faulkner

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed